History Talks: American Ambassador in Tokyo and the Countdown to Pearl Harbor

Christmas Special Edition

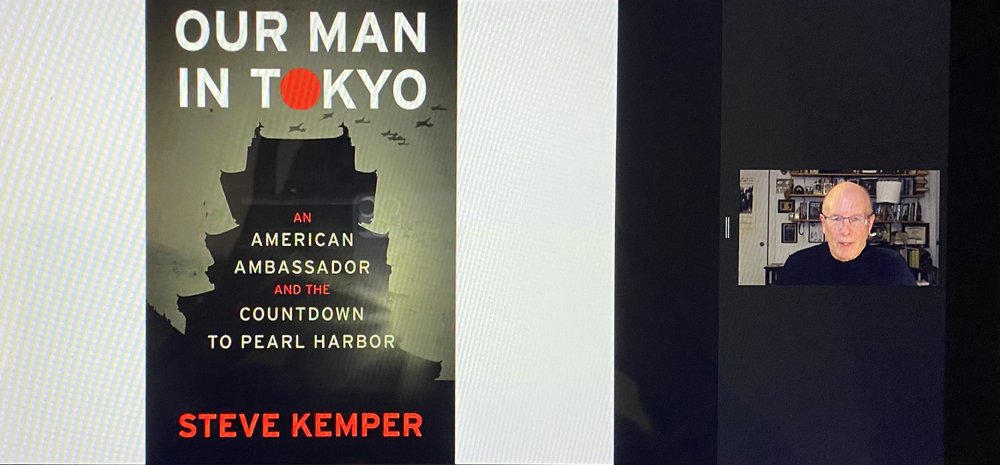

Author Steve Kemper (R) and his book “Our Man in Tokyo: An American Ambassador and the Countdown to Pearl Harbor” (published in November 2022) at an online presentation hosted by the Smithsonian Associates. All the photos in this page are borrowed from Author Kemper’s presentation.

During the decade that led up to Japan’s Pearl Harbor attack on Dec. 7, 1941 and the subsequent war between the U.S. and Japan, U.S. Ambassador to Japan Joseph C. Grew did his best to try to avoid war and warn American leaders of the oncoming storm, but his warning fell onto deaf ears in Washington, an author revealed in a recent online lecture.

Steve Kemper, author of Our Man in Tokyo: An American Ambassador and the Countdown to Pearl Harbor (published in November 2022), was the guest speaker in the Dec. 5 webinar, “An American Ambassador in Prewar Japan: The Countdown to Pearl Harbor.” It was presented by the Smithsonian Associates.

Grew was appointed as Ambassador to Japan in 1932 by President Herbert Hoover, the position deemed to be the most difficult diplomatic mission at that time. He remained in the position for the following 10 years, until a few months after the fateful attack on Pearl Harbor and the breakout of war between the U.S. and Japan.

Kemper studied Grew’s diary, correspondence, diplomatic dispatches and memorandums to put together the “behind-the-scenes narratives” about one of the most turbulent and tragic periods of U.S.-Japan history. Drawing on his new book, Kemper followed historical events during the 1930s and examined Grew’s tenure in Japan from the perspective of an American diplomat who loved his country and knew Japan well.

Joseph C. Grew, U.S. Ambassador to Japan (1932-1945)

Joseph Grew’s Background

Grew was born in 1880 to a wealthy Boston family. He studied at elite schools such as Groton School and Harvard University. Upon graduation, he made a tour in Asia, visiting China, Japan, and India.

Grew had been in the foreign service for almost 40 years in 14 posts, including Cairo, Mexico City, St. Petersburg, Vienna and Berlin. He also served on the American Peace Commission in Paris during and after World War I. In 1920, he became Ambassador to Denmark, followed by an ambassadorship in Switzerland. After serving as Assistant Secretary of State, he was named Ambassador to Turkey in 1927. His assignment to Tokyo followed, which he took up in June 1932.

Japan in 1932

In September 1931, a special group of the Japanese Imperial Army that was stationed in northeastern China to “protect” Japan’s South Manchuria Railroad made a move to occupy the Chinese province of Manchuria without Tokyo’s approval. The growing power of the Japanese military and extreme nationalism was a cause of concern for the U.S. as well as Japan’s neighbors.

When Grew arrived in Tokyo, the country was in “political chaos,” with terrorism, violence, assassinations and conspiracy. Just a month before Grew’s arrival, the infamous May 15 Incident occurred, where Prime Minister Tsuyoshi Inukai was shot to death by several young Naval officers in an attempted coup “in the name of the Emperor.” A newspaper headline in Chicago, where Grew stopped on his way to Japan, read:

Militarists Kill the Premier in Tokyo, Bomb Banks, Police in a Day of Terror; Seventeen in Uniform then Surrender.

Emperor Hirohito was 31 years old then.

The Emperor in Japan was considered a god and a divine existence. As such, he was infallible, and was not allowed to be part of a decision-making process in order to avoid accountability. In this system that was particular to Japan, he was Japan’s head of state and spiritual leader, with no actual power.

Japan had adopted the parliamentary form of Prussia and Britain. It had a Cabinet and its members. The Prime Minister was not elected but chosen by the Emperor. Also, under the Meiji Constitution, the Emperor was the Commander-in-Chief and the Military was outside of the civilian government’s control. It was allowed to nominate the Minister of War and Minister of Navy. In this system, one of those ministers could resign when the Military didn’t like what the Prime Minister was doing, causing the Cabinet to fall. This happened over and over during the prewar Japan; 17 Foreign Ministers and 12 Prime Ministers came and went during Grew’s 10-year tenure. Such was the “political chaos” that Grew had to deal with.

Japan’s Growing Ultra-Nationalism

Japan’s road to a modern nation began in the mid-19th century, with the “opening” of its doors to the world and the subsequent Meiji Restoration. Its rapid rise as a global power amazed the rest of the world, as it made back-to-back victories in wars against China (1884-1895) and then against Russia (1904-1905). But in the process, Japan experienced international “insults” – it was denied its full share of victories by the Western powers. Freedom of immigration was denied for Japanese people in the Charter of the new League of Nations in 1919. The U.S. passed the Exclusion Act which barred any Asian immigrants in 1924.

Meanwhile, ties between the U.S. and Japan were growing stronger, specifically in the areas of trade and culture.

By the 1930s, as much as 40% of Japan’s total exports were to the U.S., and 30% of its imports were from the U.S. Other Western nations such as Britain, France, and the Netherlands also dealt with Japan heavily through their colonies in the Far East.

Japan had been increasingly westernized by this time as well. Fashion, music, cinema, dance and other Western culture and entertainment were very popular, as well as Western business practice, education system, and military organizations. It was a mixture of the East and West, co-existence of traditions and modernization.

Baseball, imported from the U.S., was widely played in Japan. A Harvard graduate, Grew caught the first throw by Education Minister Genji Matsuda at the opening pitch ceremony, a game played in Tokyo by the teams of the Tokyo Imperial University and Harvard. When an American all-star team came to Japan for exhibition games in 1934, tickets for all 17 games were sold out, and 100,000 people showed up on the streets of Ginza, Tokyo to see Ruth in the parade.

Another popular import from the West was golf. An avid golfer, Grew played twice a week on average. Japan was “a golfer’s paradise” for Grew, and he often played it with his Japanese counterparts.

U.S. Embassy in Tokyo before WWII

Grew in Tokyo

At the Ambassador’s Residence, Grew entertained extensively.

It was the Ambassador’s main tasks – “to rub elbows with the people in power in his host country and gather information that could be sent back to the home government.” Grew sent in “massive” liquor orders several times a year, which he paid for himself (the Prohibition was still in effect in the U.S.).

At the time, Grew had been instructed by the U.S. government that

it was their mandate to have the Japanese leave Manchuria. But Grew had told Washington that was “never going to happen.” He thought it was critical to secure Japan’s economic and strategic interests in East Asia, and he hoped the U.S. would accommodate them through negotiations. Taking such a position made Grew popular in Japan.

Moreover, he was also a focus of the American news media. He was featured on the cover of Time Magazine (November 12, 1934 issue). His articles about Japan and Asia appeared often for the American public to read. Yet, the leaders of his home government were not looking in the same direction as Grew.

February 26 Incident

It was also the time when extreme nationalism was on a rapid rise in Japan. Right-wing nationalists were working relentlessly to undermine Japan’s relations with the West. Radicalized young military officers, politicians, and members of the police force were getting organized around the belief that Japan should return to pre-modern, traditional values. Membership of right-wing patriotic organizations soared during the 1930s.

This movement culminated in another coup attempt on Feb. 26, 1936, when extremist right-wing army officers led nearly 1,500 soldiers to attack and seize several facilities in Tokyo at the same time, including the Prime Minister’s Residence, Tokyo Metropolitan Police headquarters, the Home Affairs Minister’s Residence, Ministry of War office and War Minister’s Residence, Army Staff Office and the Tokyo Asahi Shimbun. They murdered some of the old-school politicians including Finance Minister Korekiyo Takahashi, Lord Keeper of the Privy Seal Makoto Saito, Inspector General of Military Education Jotaro Watanabe, and Colonel Denzo Matsuo, who was Prime Minister Keisuke Okada’s brother-in-law. Another target, Grand Chamberlain Kantaro Suzuki, survived the attack at his private residence with serious injuries. The mutiny was an attempt to purge the existing “corrupt” leadership in the government and for the “pure,” nationalistic elements in the Army to take control. It was all done “for the Emperor.”

Hirohito, however, did not go along with the plan. Rather, he demanded suppression of the uprising. The coup attempt failed, and the ringleaders were eventually forced to surrender. Some of them committed suicide, while others surrendered and were brought to be court martialed. The whole thing seemed to have come to an end when the Okada Cabinet resigned, Koki Hirota was appointed new Prime Minister, and the Ideological Criminal Probation Act was enacted.

Heading toward War against China

The Hirota Cabinet was short-lived. After a few more cabinet changes, in June 1937, the first Konoe Cabinet was formed, led by Prime Minister Prince Fumimaro Konoe.

Coming from one of the noblest families in Japan, Konoe was thought to have been “groomed to be a Prime Minister." His son was studying at Princeton University, and he was quite familiar with the Western ways. Grew and Konoe had dinner at each other’s residence.

Unfortunately for Japan and Grew, Konoe was influenced by the right wingers. A month after he took office, the Marco Polo Bridge Incident occurred near Beijing in July 1937, which spiraled into a full-scale war between Japan and China. Despite the initial announcement of a non-expansion policy, the Konoe government began sending more and more troops to China, following the suggestions of the right-wing militarists.

Things began getting out of hand on the front, as the Japanese began bombing cities, killing hundreds of civilians. Atrocities abounded in Chinese cities, including Beijing in December 1937, where the Japanese were reported to have killed between 50 and 200,000 people. At least 20 females of all ages were raped.

The Panay Incident

As of December 1937, major Western powers had commercial interests in China. The United States was one of them, and Japan and the U.S. were not at war.

On Dec. 12, 1937, while attacking the city of Nanking, the Japanese bombed and sank the American gunboat USS Panay, which was anchored in the Yangtze River about 27 miles upstream from Nanking. The Panay had the American flags posted, but the Japanese later claimed they had not seen them. The Japanese bombers strafed the Panay and its men on board, who were trying to swim to shore. Several Americans were killed.

Grew took the incident as the beginning of war and began packing his bags. The Japanese government promised to punish those who were responsible for the bombing and to compensate the Americans. The promise was broken almost immediately, and constantly for the next several years. In fact, the Japanese bombed hospitals, missions, schools and anything else that had an American flag on it, and then claimed it was an accident.

Grew kept protesting at every bombing. He made a list of the American facilities that had been bombed and handed it to the new Foreign Minister every time a new Cabinet was formed. By 1940, the list contained more than 300 cases of such bombings, assaults, and confiscations of property.

Grew and Washington Leaders

In May 1939, Grew took a furlough to the U.S. to talk with his bosses in Washington, D.C., starting with President Franklin D. Roosevelt. The two knew each other from Grotton School and Harvard, where Grew was two years ahead of FDR. They weren’t close but knew each other.

Grew wrote in his diary that he wasn’t sure about FDR’s abilities when he was elected President in 1932. But he became a “big admirer of FDR” over the course of the latter’s terms. It seems that the feeling was mutual between the two, since FDR reappointed Grew as Ambassador to Japan three times in a row. Apparently, Grew was too valuable for FDR to let go.

President Franklin Delano Roosevelt

Grew also met with Secretary of State Cordell Hull, whom he admired as well. Hull’s “high principles” and “inflexibility,” however, became problematic for Grew later.

Another person Grew met in Washington was Stanley Hornbeck, Hull’s Special Adviser on Far Eastern affairs. Hornbeck became Grew’s antagonist later and often tried to undermine him in the State Department, in favor of China. He distrusted Japan totally and wouldn’t hear anything about negotiations with Japan.

1939-1941

When Grew returned to Tokyo in September 1939, many things had changed. As the Japanese military was still bombing Chinese cities, the U.S. had announced abrogation of the U.S.-Japan Treaty of Commerce and Navigation in July 1939. The treaty ceased in January 1940, making Japan one of America’s unfavorable nations.

In August 1939, Germany and the Soviet Union signed a non-aggression pact, which led to Germany’s invasion into Poland in September of that year and, subsequently, to World War II.

Grew wrote that the Japanese leaders, when witnessing Germany’s initial victories in Europe, saw it as a golden opportunity for them to grab the entire Far Eastern region. France and the Netherlands, which held colonial interests in Indochina and the East Indies, were defeated by Germans.

In July 1940, upon agreement with the French government, Japan occupied northern French Indochina to block China’s supply routes. As the Commerce and Navigation Treaty with the U.S. had been abolished, Japan asked the Netherlands to sell three times more oil than previously from its territories in Southeast Asia. Japan also told Britain to close the Burma Road, which was supplying Shanghai.

In September 1940, Japan, Germany and Italy signed the Tripartite Pact to form a defensive military alliance. The U.S. reacted to this by enforcing an embargo on steel scrap exports to Japan in October. Sanctions were strengthened further, resulting in a ban of all oil exports to Japan in August 1941.

The alliance of these Axis powers was not something the Japanese political leaders had sought after from the beginning. It was the nation’s military that was taken by Nazi Germany’s initial victories in Europe. Many military officers admired Hitler. Some of them wore Swastikas. Pressure was mounting on the government for them to join the Axis alliance.

It was the military-backed second Konoe Cabinet that brought it to reality. Konoe, who came back to power again in July 1940, can be seen in a photo, dressed like Adolf Hitler at a costume party.

Japan was now part of the Axis. However, the nation’s military commitment to the Axis was immaterial at this point.

Foreign Minister Yosuke Matsuoka

In the second Konoe Cabinet, two new members later proved consequential for the future of Japan: Minister of War Gen. Hideki Tojo and Foreign Minister Yosuke Matsuoka.

Matsuoka, a “thorn in Grew’s side,” was born in poverty. He was sent to the U.S. at the age of 13 to work. He spent nine years in Oregon, converted to Christianity, and graduated from the University of Oregon with multiple degrees. He would often say that he knew more about the U.S. than anyone else in Japan.

Grew wrote in his diary that one day, he and Matsuoka had a talk, in which Matsuoka did “nearly all the talking.”

According to Grew, Matsuoka thought that he was a great man who could bring peace between Japan and the U.S., if only FDR

Talkative Japanese Foreign Minister Yosuke Matsuoka (R) talks with U.S. Ambassador Joseph C. Grew

would let him come over and talk to him. He told Grew that he could “fix everything.” Some thought Matsuoka was mentally disturbed.

As Foreign Minister, Matsuoka visited Hitler in the spring of 1941. Hitler wanted Japan’s commitment to invade Hong Kong and Singapore when Germany would invade Britain.

Matsuoka didn’t give Hitler any promise. On his way back to Japan, he stopped in Moscow and signed a neutrality pact with Stalin, surprising everyone. Japan wanted to protect its northern flank while expanding further in to the south of the Far East.

Countdown to Pearl Harbor

Grew sent a telegram to the State Department on Jan. 27, 1941, to pass on the information he collected from multiple sources that the Japanese military forces was planning a surprise mass attack on Pearl Harbor “in the event of trouble with the United States.”

Grew himself thought this “rumor” was probably ludicrous. The State Department also thought it was highly unlikely, but passed the information to military personnel anyway, who decided it was highly unlikely as well.

Yet, the plan, in fact, had been launched by Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto two months earlier.

At this point, Japan apparently thought it was in the driver’s seat. Things appeared to be going its way to push for a “Greater East Asia” while Nazi Germany was pushing its fronts in Europe. Matsuoka, riding high with his diplomatic achievements, asked the U.S. to either join the Axis or go to war against it. “If you don’t [join us], we’ll eliminate you,” were his words. Matsuoka and the Japanese military believed that Britain had already been defeated from what they were hearing from Germany. Matsuoka was eventually ousted from the cabinet in July 1941.

By this time, Japan had taken Manchuria (now named Manchu Kuo), a northern province of China, Nanking, Hong Kong, and the northern part of French Indochina. All this wasn’t achieved without sacrifice, however. Japan had paid a huge price for it – the nation spent half of its budget on its military activities, and there were shortages of everything back home, ranging from gas, oil, and metal to food and clothing. People were told to spend less and sacrifice more for the country. The Konoe Cabinet called this policy “New Structure.”

Propaganda by the military was rife in people’s everyday life. The U.S. and non-Axis powers were said to be plotting to dominate Japan in East Asia. In turn, Japan was a dove of peace. People were made to believe that somehow this fantasy could come true.

Censorship also became the norm. For American journalists in Japan, it became harder and harder to send stories back home because of censorship. Some of them were arrested after openly reporting and giving talks about China. One of them, James Young, was thrown into jail and convicted, but survived with a suspended sentence. Others were not so lucky. There was a known case where an arrested journalist was found dead under suspicious circumstances.

Disagreement between Grew and Washington

In June 1941, Germany invaded the Soviet Union. This annulled the neutrality pact between Japan and the USSR.

Grew hoped it could make Japan renounce the Axis and mend its relations with Western powers. But Japan didn’t stop its move further into southern Indochina. This triggered FDR to freeze Japanese assets in the U.S. at the end of July. A month later, he embargoed most oil exports to Japan.

Konoe now realized what he had done. Now there was a looming danger of an imminent war with the U.S., which would be even more devastating than the ongoing conflict with China. Konoe made a secret offer to Grew to meet FDR in the U.S. territory to “figure out terms that would stop the war.”

It was an unprecedented offer – no Japanese prime minister had travelled outside the country up to that point. Grew took Konoe’s offer very seriously, and urged the State Department to accept it. FDR agreed, but Hull was opposed to it. Furthermore, Hornbeck wanted to impose numerous preconditions on the meeting. Eventually, the plan was “strangled to death.”

In Japan, discussions were going on within the government about the U.S. proposals. Grew was at the Foreign Minister’s Office almost every day, asking if the Japanese were going to accept them. The answer for Grew was always “I don’t know.”

The Japanese leaders were making policies in the Liaison Conferences – high-ranking meetings attended by the Cabinet members and military leaders. Policies decided there were passed on to the Imperial Conference, where the policies were given final approval by the Emperor.

As of September 1941, the policy determined in the Imperial Conference was to continue negotiations with the U.S. [until October] and if they didn’t succeed, Japan would go to war against the U.S.

Negotiations with the U.S. to avoid war didn’t come through by the set deadline, and Konoe was forced to resign. In came Gen. Tojo, taking over Konoe as Prime Minister in October 1941. The deadline for war was pushed back according to the Emperor’s wishes. Tojo was hoping to find some ways to delay the inevitable.

Meanwhile, Hull and the State Department knew what was happening in Tokyo thanks to the program called Magic. Using this deciphering program, the State Department had decrypted Japan’s diplomatic codes and they were reading all the diplomatic traffic between Tokyo and the outside world.

Grew didn’t know anything about Magic. He was still negotiating with Hull in a last-ditch effort to stop war.

The night before Pearl Harbor, FDR sent a personal telegram to Emperor Hirohito. It stated that Japan was doing something both Japan and the U.S. would greatly regret, and urged to restore peace and “prevent further death and destruction in the world” for the sake of humanity.

The telegraph was to be delivered to Hirohito through Grew as soon as possible. However it was held at the military telegraph office for 10 hours before releasing it to Grew.

It was too late for FDR’s plea for peace to make any difference – the fateful attack on Pearl Harbor was set to begin early morning on Dec. 8, Japan time. But Grew didn’t know that. He delivered the message to the Foreign Minister’s office at midnight and went home.

Early morning of Dec. 8, Grew was summoned by Foreign Minister Shigenori Togo. Grew thought it was the Emperor’s answer to FDR’s message.

Instead, Togo handed Grew papers that said Japan was ending negotiations with the U.S.

Grew, an optimist, thought the talks would resume in a few days. It was after he reached his residence that he heard the Japanese had bombed Pearl Harbor and war had broken out between the two nations.

As a result of the bombing, 2,403 people were killed and 2,000 were wounded. Eighteen warships and 188 airplanes were destroyed. It was a total success for the Japanese, essentially wiping out the U.S. Pacific fleet.

Aftermath of Pearl Harbor

In the wake of the Pearl Harbor attack, Grew and his staff were held at the Embassy. They spent the next six months there as prisoners of war.

During that time, Grew wrote what he considered his final report from Japan - his analysis of what had happened and why.

To this 260-page report, Grew added a 13-page cover letter to FDR on his voyage back home. When he arrived in Washington, D.C., Grew went to Hull’s office and handed him the report.

As he browsed it through, Hull “got so angry” and threw the report back across the desk at Grew. He told Grew to destroy the entire report, as well as any copies that may have been made.

Grew obeyed Hull’s order but “refused to clean up the crime scene.” No copy of the original report has been found, but his cover letter to FDR (marked “not sent” at the top of it) survived. It’s now kept in the Grew Collection at Harvard, along with a “bowdlerized version” of his report. To it is attached a note by Grew, saying that 133 pages of it had been eliminated.

Steve Kemper, author of Our Man in Tokyo: An American Ambassador and the Countdown to Pearl Harbor

Today, there are plenty of records left by Grew for researchers to study. As Kemper quoted from his book at the end of the webinar:

Yet Grew documented so much of his experience and thinking in other places – his diary, his letters, thousands of dispatches to the State Department, his memoirs Ten Years in Japan and Turbulent Era – that the final report survives like a palimpsest.

Grew was in the middle of “intrigues, provocations and failed negotiations” that preceded December 7, 1941. In that sense, he was “a lens into a decade of world-shaking history” and truly “our man in Tokyo,” Kemper concluded.